As a fan of faster computers from Apple, I’m heartened by this week’s release of an. In fact, with the SPECintratebase2000 benchmark indicating speeds of up to four times faster than the Mac mini G4, this new crop of minis sounds just about perfect. I say “just about,” because of one particular issue.

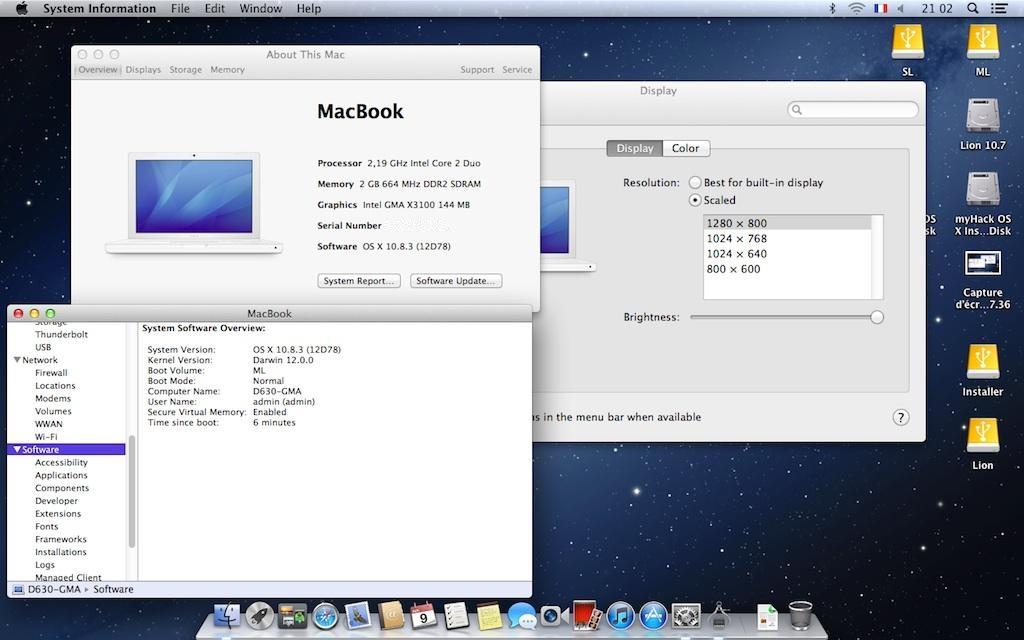

As I dug into the specs following, I noticed that the new Mac mini features a 64MB “integrated” graphics processor. In English, that means that the mini’s graphics come not from a video card (like the ATI Radeon 9200 in the first-generation mini) but from a chipset on the motherboard. This solution is much cheaper than a dedicated card, but it comes at a cost—the card gets its 64MB of RAM from the system’s RAM, and it uses CPU power to do much of its number crunching. In fact, until Tuesday morning, Apple’s mini page about integrated graphics chips: Go ahead, just try to play Halo on a budget PC. Most say they’re good for 2D games only. That’s because an “integrated Intel graphics” chip steals power from the CPU and siphons off memory from system-level RAM.

Jul 14, 2009 - I have tried every possible search I can think of and can't find a website that offers driver updates for a GMA 950! And I can't find any information.

Intel Gma 950 Driver

You’d have to buy an extra card to get the graphics performance of Mac mini, and some cheaper PCs don’t even have an open slot to let you add one. As this article was posted, now reads: Mac mini features a graphics processor integrated into the system, and one that’s no slouch, to boot. The Intel GMA950 graphics supports Tiger Core Graphics and the latest 3D games. It shares fast 667MHz memory with the Intel Core processor, for an incredible value proposition.

- Intel Graphics Media Accelerator (GMA) 950. Created at Thu, 04 Intel r gma 950 Essentially, this is the same graphic system as the GMAbut clocked at double the speed. The performance depends on the used graphics memory, clock rate, processor, system settings, drivers, and operating systems. Intel Core Duo T, 13″, 2.

- Re: GMA 950 on Mac 10.5.7 In general, the only way to get an OpenGL driver update on a Mac is to upgrade the OS, and usually only major OS updates get significant driver changes. I don't know if it's possible to upgrade your graphics card, but if I had to guess, I'd say probably not.

So, on Monday, February 27, an integrated graphics chip was something that stole power from the CPU and siphoned off system memory. As of February 28, it’s suddenly capable of supporting the latest 3-D games and is an incredible value proposition? Ah, marketing! The reality is that we won’t know exactly how good (or bad) this solution is until a mini makes it into Macworld Lab for real-world testing. Personally, I’m not worried about gaming, but I’m curious as to how well it will work with six or seven large applications running when it’s then asked to do something that’s CoreGraphics-intensive—like opening 10 widgets in rapid-fire fashion.

Also keep in mind that the mini is not a gamer’s Mac. Anyone buying a mini to play or Doom 3 is going to be disappointed.

It’s Apple’s lowest-price Mac, the starting point for Mac performance. As such, it’s important that it do well in typical non-gaming tasks, and support OS X’s graphics needs well. Beyond that, if it happens to run some of the 3-D games in a reasonable fashion, it’s a bonus. But the question about the mini’s graphics support, although very important, isn’t what stuck with me when I read about “integrated graphics.” Instead, I found myself thinking more about what the move to an integrated graphics chip meant for the future of Apple hardware. For many years, PC builders have used such chips on their entry-level machines.

But Apple, mainly due to having no such option with the Motorola/IBM processors, had never gone this route before. As such, my initial thought about the mini’s new graphics chip wasn’t performance related.

Instead, it was more like: “The Mac mini is the first Apple Dell!” Or to put it another way, I found myself thinking “cheaper hardware in cheaper boxes.” And since that’s the same thing everyone else offers, that led to an immediate follow-up thought: oh no. But is that really a valid concern? Will Apple become nothing more than an industrial designer of nice-looking boxes filled with generic hardware? And even if that does happen, should that worry me? About Dell As you probably know, Dell is one of the largest sellers of Windows-compatible machines on the planet.

And they got to be huge, not by having the best R&D departments and manufacturing lines but by figuring out how to build and deliver machines faster and cheaper than everyone else. In contrast, Apple had an early history of designing and building everything itself—the company owned its own manufacturing plants in places like Sacramento, Calif., for many years. Generalizing a bit (as I’m not privy to the inner workings at Dell), Dell purchases motherboards, keyboards, RAM, mice, hard drives, the operating system and BIOS, CD and DVD drives, cables, monitors, speakers, video cards, networking chips, and various other PC components as cheaply as possible from any number of suppliers (well, there’s only one Windows OS supplier, obviously). Dell then uses the most efficient assembly methods possible to put those parts together inside the only thing that really makes a Dell a Dell—the case.

So here we have a company that sells $15 billion worth of Windows computers per year, and yet as far as I know, doesn’t manufacture a single thing. Instead, the company is the world’s most efficient assembler of parts, some of which it specifies the design for, and others of which are industry-standard. That bundle of parts is then nicely wrapped up and delivered in a case stamped with the Dell logo, all powered by Windows. And Dell does this very well; it makes some nice systems that perform admirably—I had a Dell at my last job, and it was one of the fastest and quietest machines I’ve ever used. About Apple Now consider Apple. For years, Apple had a serious case of using technologies that differed from the rest of the computer business. The auto-eject floppy (remember those?), the NuBus interface bus, the Apple Desktop Bus (ADB), Apple’s seemingly-never-ending string of unique monitor interfaces, and even SCSI disk interfaces were all technologies primarily used by Apple.

Many of these were even developed in house, through Apple’s own R&D department. These technologies were more costly than industry-standard alternatives, and in many cases, tied Apple to a sole supplier. (Only Sony made the auto-eject floppy, for instance.) Even the motherboards were an Apple-specific part, including quite a few Apple-designed integrated circuits. Most companies that sell Windows PCs (excluding the motherboard firms that have gotten into the PC manufacturing business) don’t do anything with motherboards or chips beyond purchasing and assembling them. For the consumer, all this technical wizardry meant really expensive systems.

Remember the? Introduced in 1990, it cost around $10,000 at the time. Adjusting for inflation, that’s about $15,000 in today’s dollars.

(Granted, costs have dropped greatly on other components since then, so the IIfx wouldn’t cost anywhere near that much today.) Even in its time, it was a very expensive machine—comparable DOS/Windows machines were substantially cheaper. To reduce costs and improve parts availability, Apple has been slowly moving away from Apple-created technologies towards industry-standards. Hence, NuBus became PCI and PCI Express; ADB became USB; monitors are now connected via DVI or VGA standard plugs; and hard drives connect via ATA or SATA. In other cases, Apple has helped its technologies become standards (FireWire), which helps insure multiple manufacturers and lower costs. These changes have helped lower the price of the Mac, though they’re still more costly (in general) than a typical PC. The switch to Intel According to Apple, the was justified on a “power per watt” analysis of Intel versus IBM chips.

However, there are other advantages as well—namely, access to even more industry-standard technologies. Intel is a huge company that drives a lot of activity around the Intel standard. For Apple, this means access to lots of technologies that are already in use on millions of PCs. The integrated graphics chip is a perfect example.

With the G4 chip, Apple didn’t have this option available, unless it wanted to custom-design an onboard graphics chipset itself. That would clearly be an expensive proposition, so sticking a third-party card in the low-end mini made the most sense.

But with an Intel-based mini, Apple suddenly had access to an already-developed, ready-to-use integrated graphics solution. Economically, it makes a lot of sense for an entry-level machine, given the target audience. Performance-wise, we’ll have to wait and see if it was a reasonable decision. Is the new mini a ‘cheap’ machine? As I mentioned earlier, the mini is not the machine to buy if you want to play the newest 3-D games. Nor is it the machine to buy if you want to work in all day, producing the next Star Wars.

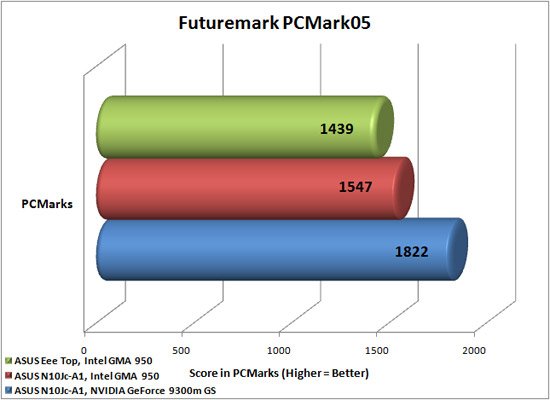

It’s Apple’s entry level Mac, the cheapest one you can buy. (Granted, it’s missing a keyboard, mouse, and screen, but it’s still pretty cheap.) As such, cost considerations do come into play. That said, I must admit that when I read “graphics chipset,” I cringed and immediately thought of nothing but abysmal graphic processing. In so doing, however, I made a couple of major mistakes. The first mistake was not knowing anything about the GMA950’s performance. On paper, at least, this chipset is technically at least as fast as (if not faster than) the Radeon 9200 it replaces. And the 9200 was also not much of a card for 3-D games use either—I found a couple of Doom 3 benchmarks that showed the 9200 scored around nine frames per second at 800-by-600 resolution, while the GMA950 managed to reach all the way to 13 or so.

Real world tests will show, of course, if the new chip will outdo the old card in daily use. I still greatly dislike the concept of sharing RAM and CPU with the graphics card, and the 80MB of RAM reserved for the video card (64MB for the card and 16MB for a frame buffer) will effectively turn the mini into a 432MB machine. Setting aside the performance question for the moment, my second mistake was a classic “can’t see the forest for the trees” mentality. By focusing on the graphics change, I missed everything else that Apple seems to have done right with the new mini:.

Intel Core Duo chip is significantly faster than previous G4. 2MB shared L2 cache vs.

512KB on-chip cache. 512MB DDR2 RAM at 667MHz vs.

256MB DDR RAM at 333MHz. Serial ATA hard drives instead of Ultra ATA (and the low-level machine has a 60GB drive, up from 40GB). 667MHz system bus vs. 167MHz system bus.

Composite and S-Video outputs. Gigabit ethernet vs. 10/100 Ethernet. Built-in AirPort Extreme vs. Extra-cost option.

Combined optical digital audio input/line in and output/headphone out vs. Headphone out. Four USB ports vs. Two USB ports. For all of that, the cost increased $100 for the base model. The AirPort card alone is a $99 retail item, so they’ve clearly added a lot of value and performance to the machine.

My main concern is still the performance of the graphics chipset. Will the improvements in system bus, CPU speed, cache, and memory speed make up for the sharing of CPU and RAM with the graphics chipset? And how well will the chip handle CoreGraphics’ requirements with a number of applications running and using up RAM? If the GMA950 can do an acceptable job in these areas, then the new mini will be a real winner in my book. I have one on order, and will start running my “Rob Griffiths’ benchmarks suite” once it arrives.

Macworld Lab also has a machine in house to do more official testing and evaluating of the mini’s performance. So is the new mini really an Apple Dell? In many ways, it is. It’s got a lot of industry-standard technologies, including the new onboard graphics chip. As noted, this is what I originally focused on when I heard about the new mini.

In so doing, though, I overlooked the one fact that will keep Apple from ever turning into just another box maker. It’s also the reason I’m quite comfortable with my decision to put a mini in the labs for daily use. And that fact is OS X. The key difference between Dell and Apple is that Apple also owns, develops, and modifies the core operating system that runs their machines. Dell, on the other hand, basically gets whatever Redmond sends them every few years.

As much as Dell would probably love to ship a machine with Vista on it today, it can’t. The release schedule for their first Vista box lies completely in Microsoft’s control. Dell will get the same version of Vista as every other vendor, leaving only price, hardware features, and case design as differentiating factors. Apple, on the other hand, owns the operating system. If it wants a new feature to support some new hardware design direction, it can simply add it in as needed. They can also create those amazingly compelling applications (iPhoto, iMovie, iTunes, iDVD, Mail, Safari, etc.) that make using OS X on Apple hardware such a joy.

Add-in the best industrial designers in the business, and you have the recipe required for Apple to continue building cool, useful hardware and software. Inside the box, the parts may look more like a Dell, but in terms of use, a Mac will always be a Mac as long as it’s running an Apple-designed operating system. So despite my worries about the graphics performance of the new mini, I’m not concerned that this is the general “beginning of the end” of Apple hardware as I know it.

As long as the company still owns the OS, designs amazing applications, and wraps them together in great industrial designs, I’ll continue to be a happy customer.